Tomorrow I’m teaching and co-leading the first class of a four-session virtual series, The Circle Way: A Deep Dive. I’m doing so at the invitation of my friends and colleagues Rowan Simonsen and Amy Lenzo. Together we’ve been meeting and creating this series for the last three months. Rowan is a deep soul. His pace and skills are very grounding. Amy is the sweet spot between genius and deep caring human. We’ve known each other for years, initially through The World Cafe community.

Yesterday I was sorting through my notes and scribbles from these three months to clarify what I want to share in the class. I was facing the challenge of having a lot to share — a deep dive welcomes this — but needing to be quite discerning about how much to share and how to knit it into a simple narrative that can help people make sense of many important nuances of The Circle Way. The teachings will be in 20 minute chunks, followed by an essential engagement in smaller groups.

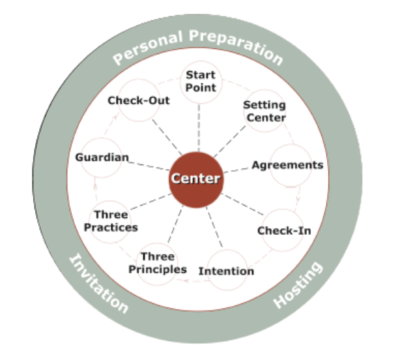

A key structural distinguisher of The Circle Way compared to other forms of circle and other participative leadership forums is “The Components Wheel” above. It’s the basic structure that defines the practice that is The Circle Way, originating from Ann Linnea and Christina Baldwin and their teachings over the last 25 years. As Christina has shared with me, “we wanted the lightest structure to help correct what goes awry in most contemporary forms of meeting.”

What I really enjoyed in yesterday’s preparation was playing with each of the components and creating a bit of inquiry: 1) What is it like without this component — what tends to happen? 2) What is the basic and essential definition, practice, or todo of the component? And 3) what is the deep dive importance of this component — what is the nuancing of it’s practice that can transform the experience from a meeting to a moment-maker?

As example, consider the component of a Check-in. A Check-in is a beginning. A chance for each person in the circle to speak a bit to the whole group (or to a partner or small group if the number of participants is significantly high).

Without a check-in, when it is absent, what do we tend to get in meetings? Often it can feel like a jarring start. Bam! Right in to the content. Right in to the first third of the movie without setting the scene. No real attention to the people that are showing up in the room and how they are. No welcome of the unique circumstances that may be influencing people who are about to work together. Absence of check-in often leads to absence of people showing up and being more fully attentive together — more distracted, less connected.

The basics of a check-in involve giving each person a chance to respond to a question, whether a sequential passing of a piece or in popcorn style, speaking when ready regardless of order. My teaching colleague and friend Amanda Fenton recently posted a piece on Questions for Check-ins — she includes many important simple choices for how to begin (and how to see the deeper dive of this component). Check-in gives you a kind start that is much more likely to lead to the things most of us are looking for in our meetings — fulfillment, productivity, and appreciation. Good, right.

My check-ins tend to invite response to two questions — “Is there anything you need or want to say that helps you be more present in this meeting together?” Responses are always interesting. From “I need a cup of coffee” to “my babysitter was sick today and I had to juggle child care.” Regardless, they create a glimpse into who is sitting next to us or across the table. The second question is usually about the work at hand — e.g., “What have you seen in the last week (or day, or hour) that further amplifies the need for what we are doing together?” This kind of question really elevates purpose in the room. Presence and purpose together — even a taste as one of the first things we do in meeting — wow!

The deep dive is more than giving each person a turn to speak. It’s definitely more that being nice together in the democracy that is dialogue. The deep dive is more than using a talking / listening piece. The deeper dive of check-in is about getting present and showing up to give full attention to one another and to the task at hand. In a rather multi-tasked population, most being pressured to squeeze much into short periods of time, paying attention only to what is in front of us has become difficult, right. Gotta think about the next meeting while I’m in this one. The deep dive of this component, check-in, is about welcoming a moment of wholeness for individuals and the group that interrupts contemporary meeting patterns of fracture and distraction. The check-in, for the moment, forms the flock, so that we can go differently together.

I’m looking forward to encouraging participants in this virtual class, and in the five day practicum and retreat that Amanda and I offer together this August to notice what happens when the component is not in place, and also to give keen attention to what is going on in such simple, and yes, I would say, liberating structure that changes how meetings happen and how human beings come alive in them.

Please join us. Not too late for the virtual class. And this summer’s practicum is starting to fill with really good people.